For five years MicroProse had enjoyed a golden age; since Sid Meier’s Civilization’s release in 1991 the company had undergone a period of prosperity and recognition, achieving acclaim though many other Sid Meier games. However when the company was sold out and when consolidation led to layoffs a chain of extraordinary events led to one of the most unusual and disastrous developments to befall the Civilization name, one that significantly diminished the reputation Civilization had built.

Swirling Maelstrom – Call to Power I and II

‘Call to Power will be allowed to hang out at the same bar as the Civs and Alpha Centauri, but will have to buy them drinks.’

– Niko Nirvi, reviewer for Pelit magazine and in general a major icon of Finnish gaming.

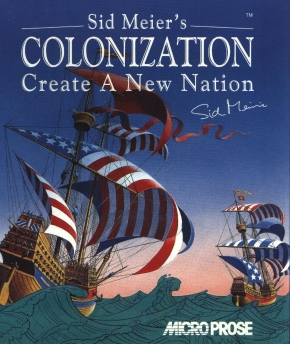

But before all that let’s take a brief detour and reflect on the legacy that Sid Meier managed to create, not the Civilization series itself but rather the effect the franchise has had over the game development industry as a whole, dating as far back as Civilization I. Starting with Sid Meier himself – Sid in the course of his career has made a multitude of games, mostly strategy games, however Sid made two games in particular that are recognized as spinoffs from the Civilization series; Sid Meier’s Colonization in 1994 and Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri in 1999. Colonization was a different kind of turn-based strategy, certainly so compared to Civilization; unlike Civilization where you build an empire from the very beginning Colonization is a game where you build a self-sufficient nation out of a European colony in the height of the Age of Discovery. A number of the typical systems from Civilization exist in Colonization – movement and exploration, goody huts, tile yields – however Colonization bought with it truly unique systems for concepts such as domestic trade, professions, even the victory is totally unique to the game as in order to win your colony had to declare its independence and then defeat the Crown’s army. Alpha Centauri is a game that’s much closer to a standard Civilization game, but even so the game has its own unique traits. The game introduces a narrative for the first time, based on the Scientific Victory of the previous games the story tells of the crew of the spaceship Unity, forced to abandon their ship after a reactor malfunction and the death of the captain. With seven escape pods the crew scattered all over the alien planet and would over time develop their own faux-civilizations. Once again Alpha Centauri added standard Civilization systems such as exploration and combat, however some of the most audacious concepts came from Alpha Centauri such as social engineering projects to bolster the faction’s bonuses, add-on components as opposed to entire units allowing for complete customization of a faction’s army, and completely unique barbarians in the forms of alien life – unique creatures that paralyze enemies or act as natural artillery – and the very planet being semi-sentient. Many of the systems and concepts in Alpha Centauri were later appropriated into the 2014 spinoff Sid Meier’s Civilization: Beyond Earth.

One of the many popular games MicroProse published was Master Of Magic, largely considered the godfather of fantasy strategy computer games.

Remaining with MicroProse; the company isn’t simply known for its association with Sid Meier, although it does owe a good deal of its acclaim to him. Simtex was a much smaller game company that was founded in 1988, by publishing the games MicroProse along with Simtex released two well-known games at the time – Master of Orion in 1993 and Master of Magic in 1994. Orion was another science-fiction TBS game where instead of dominating a new planet one attempted to conquer an entire region of space, constructing spaceships and expanding one’s colonies on planets. Magic was a game much closer to Civilization games in that units traveled over tiles and explored the world to uncover the fog of war, whereas Orion used predetermined lengths between systems in a completely open universe. Both Orion and Magic gained similar notoriety and high praise comparable to Civilization, as well as each having their own legacies in their genres; Master of Magic served to be the inspirational platform for games like the Age of Wonders series and the recent Worlds of Magic game. A little known fact about Master of Magic is that a sequel to it has been mentioned and discussed sporadically since 1997 when Steve Barcia, designer of the game and founder of Simtex, announced one for the following year before Simtex itself was forced to close. MicroProse themselves also attempted a sequel but cancelled the project as the company fell into financial troubles in 2000. Quicksilver Software and Stardock both tried to create the sequel by obtaining the rights to do so, but this led to no avail as negotiations with Atari fell apart. Master of Orion however became its own franchise and inspired games such as Starbase Orion, however the biggest news is Wargaming.net purchasing the franchise from Atari and developing a reboot of the game – Master of Orion: Conquer the Stars was released in August this year.

Age of Empires broke the mold compared to other real time strategy games, the game however held firm its appeal with the likes of Warcraft and Dune II.

Lastly to the wider market; for all of the most influential games in history their legacies rarely occur in a vacuum. Civilization I co-designer Bruce Shelley left MicroProse at the end of 1992 to join another motley company at the time, Ensemble Studios, where he brought his experiences working with Meier to create a real-time strategy game – the now infamous Age of Empires. Previous RTS games of the time featured a science-fiction or fantasy setting; Age of Empires was the first RTS game to feature history as the setting. Many of Civilization’s systems and motifs are present in the game; civilian and military units, a dense technology tree, a system of trade between docks. Initially the game gained minor yet on the whole positive reviews; the game itself had an endearing charm and unique quality that helped Ensemble create its own foundations in gaming. Age of Empires II: the Age of Kings solidified Ensemble Studios into history as the game was universally acclaimed, this in turn forged Ensemble into a studio exclusively aimed towards real-time strategy and devoting almost the entirety of its time to the Age of Empires series – producing a total of six RTS games, three of which are Age of Empires and a fourth as a spinoff, Age of Mythology. The success of the Age of Empires franchise and the detailed look into the major periods of history within its games would ultimately motivate another game developer to try to string all of the periods together and approach the broad range of Civilization – that studio was Big Huge Games and the game was Rise of Nations. Similar to Age of Empires the development of Rise of Nations included a former Civilization designer, in this case Civilization II lead designer Brian Reynolds left Firaxis Studios in 2000 to join Big Huge Games and design Rise of Nations. Rise of Nations is in no uncertain terms a true cross of the TBS and RTS giants, Civilization and Age of Empires; the game incorporates many systems from standard RTS games such as resource management, specialized buildings for the economy and the military, buying and selling resources, etc. with some of Civilizations’ own concepts at the time such as founding cities, national borders, scientific research as a resource and rare resources acting as typical resources in a Civ game. Rise of Nations gained instant and great acclaim, often considered the marriage of two of the greatest computer games. Again, similarly to Ensemble Studios, Big Huge Games created its own legacy from Rise of Nations, and continued to develop the franchise – in fact Big Huge Games collaborated with Ensemble Studios to create Age of Empires III: the Asian Dynasties, the last Empires game for Ensemble Studios before it closed down in 2009.

All these games and others after owe at least part of their inception to Sid Meier and Civilization, and as each new strategy game in the future comes to pass the effect that the franchise has and will still have today will continue to reverberate within the concepts and systems in each and every game. Returning back to the original thesis, not long after Civilization II released MicroProse fell into downward spiral. By 1996 Bill Stealey had already left the company; as the managing director at the time Stealey sought to port many of MicroProse’s flight simulators into console devises and arcade machines, however these ports turned out not to be profitable and as a result the company fell into debt. In August 1991 MicroProse filed for an Initial Public Offering – the company transformed its shares from privately owned to the general public for purchase – in order to raise US$18 million and recoup its losses, that however never reached its total and so by December 1993 Stealey chose to sell the company outright to Spectrum Holobyte. Gilman Louie, president of Spectrum Holobyte was actually rather good friends with Stealey at the time and Stealey convinced Louie to help the company lest it fell into the hands of the banks. The UK branch of MicroProse and its satellite studios closed down and in fact a group of former staffers joined a new company – Psygnosis – in order to attract more ex-MicroProse staff; just months later Stealey himself left MicroProse with Spectrum Holobyte buying out his shares. Bill Stealey is still in the computer game business today; after MicroProse he founded another company – iEntertainment Network, formerly Interactive Magic – and is currently the Chief Executive Officer of the company.

The unique concepts from Colonization such as Founding Fathers and physical Trade Routes placed it as one of the best games of its time, comparable to Civilization itself.

Under Spectrum Holobyte MicroProse continued to produce or publish more popular computer games such as the Magic: the Gathering computer game, the Star Trek: the Next Generation series, UFO: Enemy Unknown – the first game of the X-COM series, Master of Magic, Sid Meier’s Colonization and Sid Meier’s Civilization II. Learning from Stealey’s example and being burdened by insufficient finances the company concentrated its efforts on PC games over trying to port to other devices. After the initial purchase MicroProse continued as a separate subsidiary company under Spectrum Holobyte until 1996 when the parent company decided to cut the majority of MicroProse staff to cut costs, not long after Spectrum Holobyte moved to consolidate all of its titles under the MicroProse brand. Sid Meier, the remaining co-founder of MicroProse, along with Civilization II designers Brian Reynolds and Jeff Briggs chose to leave MicroProse as the layoffs took place in order to found their own company; on January 5th 1996 the trio founded Firaxis Games. In the formative years of Firaxis the company continued to develop strategy and tactic games, releasing Sid Meier’s Gettysburg! and Antietam!, and Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri.

However 1997 would prove to be the turning point for both companies, and also for a third game company – Activison, the aggregator to it all. In April Activision acquired the rights to the ‘Civilization’ name from Avalon Hill – the board game company that published the original Civilization board game into the US – for use in their own games. As benign as the decision was, or at least the perception of which, it would lead to a much bigger event; meanwhile on October 5th GT Interactive Software announced it had reached an agreement with MicroProse to acquire the company for US$250 million in stock and that the Board of Directors from both companies agreed unanimously. MicroProse stock skyrocketed to $7 a share at the time of the announcement and it was expected that the deal would be completed by the end of 1997; however in November MicroProse became the target of a legal battle against Avalon Hill and Activision over copyright infringement. In response to the suit MicroProse bought Hartland Trefoil – the UK board game company that originally conceived of the Civilization board game – the following month, the move was to establish MicroProse as the “preeminent holder of worldwide computer game and board game rights under the Civilization brand.” By December 5th the scheduled acquisition was cancelled; according to the CEOs of both companies the time was not right to for the deal to take place, however it was later discovered that the deal was cancelled not due to poor timing but to a disagreement over how the two companies would write off its research and development costs. After the announcement of the deal’s cancellation MicroProse stock fell just as much as it raised, down to $2.31 a share.

Thus at the start of 1998 MicroProse launched its counter-attack. In January the company counter-sued Avalon Hill and Activision for a multitude of claims such as false advertising, unfair competition and unfair business practices, due in no small part because of Activision’s intent to create and publish ‘Civilization’ games. The attack proved to be successful; in July that year the two parties settled their case out of court with MicroProse profiting from it greatly – Avalon Hill was ordered to pay MicroProse damages of US$411,000 and more importantly MicroProse kept all the rights to the Civilization brand. However, in the eight months that Activision and MicroProse were fighting over the name Activision had already began to develop its first Civilization game, as a result of the fact Activision did gain the license to apply the Civilization name to this game from MicroProse. This game was Civilization: Call to Power.

Whatever one’s opinion is for Civilization: Call to Power the concepts and ideas the game presented were original and in turn breathed new life into the game format, nevermind its unusual inception.

Releasing in March 1999 the game was very ambivalent; the game featured new ideas and unique concepts as well as contemplating the world’s future for the first time in the series, but the game was also hamstrung by the fact that it had a radically different user interface and was a rushed build leading to a game full of bugs. While information of the development of the game is not presently available a number of the game’s systems and ideas suggest a very wild imagination from William Westwater, the lead designer of the game. The biggest feature the game offers is the ability to not only exist into the future by playing games as far forward as 3000 AD, but also to research and build the future by expanding the technology tree to include possible technologies that allows the colonization of the seas and the skies, the eradication of pollution and the discovery of alien life. With future technology come futuristic concepts such as terraforming the sea to suit deep ocean cities, large exoskeletal combat machines, and a microchip implant that bolsters the human immune system. Call to Power also introduced some of the most resent inclusions into the Wonders of the World pantheon such as Stonehenge, the Hagia Sophia and Hollywood.

Yet for all of its unique charm and graphical enhancements over Civilization II, Call to Power was fundamentally flawed in its design; while some of its concepts were inspired others were hindrances, for example the replacement for the Settler’s or Engineer’s ability to build tile improvements came in the form of Public Works or PW points. This was a system where a percentage of the total production output of the empire was split from the cities’ production queue and pooled into a tally where the player could then purchase tile improvements to place and gain their benefit. In theory the system was designed to mimic a more modern application of infrastructure where instead of a designated unit moving to a targeted tile and building the improvement on site a theoretical fraction of the empire’s population is active at all times where they build improvements in various locations. The system was complicated and its application was hard to fully grasp. Diplomacy was bland; while the game featured 41 civilizations none of the leaders had any unique personalities, one could play against Alexander the Great, Winston Churchill, George Washington or Gough Whitlam and every artificial intelligence would behave and operate exactly the same as the rest. Since MicroProse had possession of the Civilization brand Activision decided to steer clear of any conflicts in intellectual property, as a result many technologies and all of their wonders were completely different – Archery became Alchemy, Horseback Riding became Stirrup, Chemistry became Cannon-Making and Combustion became Mass Production, also entirely new wonders and concepts such as the Sphinx, the Philosopher’s Stone, the East India Company and the London Exchange.

It was the small details that unraveled the gloss of a new game. The game received mixed reviews on the whole; some citing the innovations in trade routes and combat with stacked units as laudable concepts but also found the diplomacy lackluster, the obvious and fragrant lack of assets from the previous games, and worst of all the lack of immersion. The score range for Civilization: Call to Power varies between quite literally good and bad; Finnish magazine Pelit rated the game 85%, GameSpot gave CTP a 6.7 fair score, IGN gave the game 4.8 – scoring highly in its presentation but poorly for its content. However, for all the turbulence of Activision’s game the decision to release a sequel was unexpected; without the ability to regain the license to the Civilization brand the name would need to be altered to just Call to Power II.

Call to Power II suffered great losses compared to its previous game; this was largely due to the fact that the ‘Civilization’ name was barred from the game and as a result, without the prestige of the brand, the game fell into obscurity.

The game released in November 2000 – twenty months after Civilization: Call to Power – and with a team of designers led by David White there was a sense of improvement about the game; one of the problems of CTP was the user interface and the design team boasted an improved UI in the sequel. Upon the release the game indeed had a number of improvements; chiefly the diplomacy system was improved with increasing the options in negotiations such as non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. Balance was improved broadly by increasing the maximum army size and improving the economic system in order to improve the benefits of terrain. CTP2 also introduced city and national borders, the progenitor to the culture system and city borders in Sid Meier’s Civilization III.

The biggest addition in Call to Power II was the support of mods; with a significant fraction of the games rules and AI scripts stored in text files and the game itself contained SLIC – a fully documented scripting language – allowed for the vast majority of the game to be modified. The sole patch for CTP2 enhanced SLIC, allowing the creation of fan-made mods that dramatically changed the gameplay. The biggest exclusion in Call to Power II was the removal of space colonization and the alien life victory condition; it was discovered that space colonization slowed the late game right down and so was removed for that reason. As for alien life the entire system and victory was also removed to allow for a new victory condition based on Gaia Sensors and the Gaia controller wonder – the Solaris Project.

However even this game was riddled with balance issues and bugs and through the work of the community of modders, especially from the Apolyton Civilization Site, the fans themselves sought to improve the game after its release. Upon its release Call to Power II again received mixed reviews; GameSpot handed the game a 7.2 good score, citing the improved interface, graphics and sound and its replay-ability while pointing out its again poor diplomacy, tactical control during combat and the bad AI. IGN yielded a score of 6, again scoring highly for its presentation and poorly for its graphical and audio contents. However this was not quite the end for Call to Power; as Activision was moving on to its newer games the company stopped providing patches for the game. As a result the Apolyton Civilization Site became the de facto support centre for technical issues and mods for Call to Power II. Eventually the members of the site contacted Activision to ask the company to release the source code of the game; after a number of months Activision exclusively released the source code to the Apolyton Civilization Site in October 2003. The move allowed for the online community to support CTP2 themselves with their own patches in perpetuity – the community have done so now for nearly a decade with their most recent revision in June 2011.

As mentioned before 1997 was a definitive time for MicroProse, Activision and Firaxis; for MicroProse the litigation war with Activision may have played a role in the cancellation of its merger with GT Interactive Software, but it led to negotiations with Hasbro pursuing to purchase the company. MicroProse would continue to produce games as a subsidiary company for Hasbro Interactive until 2001 and then for French game publisher Infogrames until November 2003 before Atari Inc. – the Infogrames brand name changed to Atari Inc. at the time – closed the last MicroProse development studio in Hunt Valley, the original studio in fact. For Activision while it had nothing to do with the lawsuit itself Activision began a longstanding expansion of its partnerships and acquisitions; starting with Raven Software in 1997 Activision would eventually partner with Marvel Entertainment, LucasArts and Sega, established game development studios, while purchasing Treyarch and Infinity Ward, companies well known for their involvement in the Call of Duty franchise. In 2008 Activision merged with Vivendi Games, who themselves own Sierra and Blizzard, transforming the Blizzard studio to become Activision Blizzard.

For Firaxis the effects of the lawsuit would take a much longer time to ripple out to the company, and this will be covered in the third part. This concludes the second part. The next part will discuss how Sid Meier would be handed his original creation back to him through Infogrames and then permanently by Take-Two, Firaxis’ current parent company, and also the bold decision by Sid and his designers to inject new concepts into the series, many of which would change and revolutionize the franchise itself thought Sid Meier’s Civilization III and IV.